12.24.2013

12.17.2013

Pill Heds

I've been thinking about drugs names. I don't think I'm alone in my occasional scrutiny of these mysterious, often ridiculous, sometimes brilliant confabulations. (The pharmaceutical business spends a good chunk of their budget on branding and naming and I think this tangential element of design justifies my assessing the results, no? I'm not going into the logo design here, but see this amusing step by step "review" of Ablixa.)

Huge potential money-makers like psychopharmacological agents and erectile dysfunction buttresses have particularly high stakes in naming and design. According to Medscape the cost in 2001 of consultation on naming alone ranged from $100,000 to $700,000. Elsewhere I read the numbers are "easily" $500,000 up to a couple million.

Each drug receives 3 names:

• the chemical name—usually a string of prefixes, numbers and a lot of "ethyls" and "phenyls"

• the International Nonproprietary Name (INN, also known as the generic name)— these names are created from a standardized group of "stem" components which represent different classes of drugs (eg. anti-inflammatories, antidepressants)

• the brand name

here's an example:

- chemical name — 7-chloro-1,3-dihydro-1 methyl-5-phenyl-2H-1,4-benzodiazepin-2-one

- generic name — diazepam (-azepam is used for many antianxiety agents)

- brand name — Valium

Going through what must surely be a gauntlet of committee presentations and focus-grouping, how on earth do names like Xalkori and Xofigo see the light of day? The New York Times noted that "drug makers have favorite letters, and they run the gamut from X to Z." They quoted James Dettore of Brand Institute and explained;

"the letters X, Z, C and D, according to ... "phonologics," subliminally indicate that a drug is powerful. "The harder the tonality of the name, the more efficacious the product in the mind of the physician and the end user," he said."According to Slate, though, there might just be a computer algorithm behind all those Xs:

During tough financial times... many drug manufacturers skip human consultants and use computerized algorithmic name generators because they just want something that will get quick approval from the FDA and don’t care how ridiculous the name looks or sounds. //My not-so-empirical approach to looking at drug names

the word-- how does it sound? how does it look?, associative images–– what does it sound like? what does it bring to mind?, appropriateness–— how well does the name work for what the drug does?

Successes:

Ambien—pretty good at conveying a zoned-out calm, perhaps a little too techno

Zoloft— its propping you up, get it?--holding you zoloft

Viagra— brilliant— it's vigorous, it's vital, it's Niagra Falls for chrissakes

Abilify— "this antidepressant has abilified me to be functional!"

Keppra— Strangely elegant and aloof, like the name of an ancient Egyptian deity. Not bad for an anti convulsant

The not-so-greats:

Vioxx— a vanquished Transformers villain— anti-inflammatory now off the market

Viibryd—looking like something you'd find at IKEA (thanks Andrew) this antidepressant doesn't even have an aspirational quality. plus the sound of it seems a bit too manic for a mood stabilizer

Coumadin—a blood thinner that sounds like a mid-level bureaucratic title of the Ottoman Empire; its generic name, warfarin, sounds like a strategic conflict board game

Effexor— this antidepressant reminds me of Gigantor, Space Age Robot

Aubagio— sounds to me like an Italian restaurant you'd find on Staten Island, odd association for drug to treat multiple sclerosis

Stalevo— treats Parkinsons disease but looks like it's a city in Serbia

Simponi Aria— is it part of an Italian opera? an obscure part of the brain (see Wernicke’s area)? No it treats rheumatoid arthritis. Perhaps it leaves you singing.

Fails:

Fungizone— targets potentially fatal fungal infections; the name sounds appropriate in a blatant ham-fisted way, but I would not like to tell people I was on it.

Latuda—an antidepressant that seems more like a vulnerable area of the lower back; see "phonologics"mentioned above—this drug doesn't sound man enough to make me happy

Lamictal— looks like a term for a pus-forming condition—not so good for a mood stabilizer/anti convulsant

Zortress—suppresses the immune system but sounds like a 1980s video game

Zingo— just completely wrong

Labels:

collections,

momentary obsessions,

sound/music,

words

12.10.2013

Cloisters and Cardiff

The Cloisters itself— a faux medieval abbey which houses much of the Metropolitan Museum's medieval collection—can strike one as characteristically American. If you think too long on its conception it can color your visit, or at least it did mine: rich diletante (George Grey Bernard) collects bits and pieces of medieval architectural details from around Europe and imports them here; a medieval pastiche financed by another rich American (John D Rockefeller) is constructed to house them; land both immediately surrounding the complex as well as across the river along the New Jersey palisades is bought up to preserve the view. A testament to American wealth and cultural boldness— buying up history wholesale and bringing it home. Thus the Fuentiduena chapel is actually an apse from one location, statuary from another, and a fresco from yet another, inserted into a "chapel" built in 1938. Throughout the building there are door frames from France housed with pillars from Spain flanking rooms made from Netherlandish accoutrements. Still, I dont really mean to criticize. Its a lovely haven in Manhattan and the gardens with researched, period-appropriate plantings are wonderful in and of themselves.

Labels:

architecture,

art/design,

collections,

new york,

sound/music

11.18.2013

The ABCs of B. de B.

|

| You can see the entire collection of alphabet prints at our shop: www.b-de-b.com |

|

| Some of the other offerings in the scrapbook are on the more macabre side. |

The Background:

At an Ephemera Fair a couple years ago, Doug, Sam, and I bought a large scrapbook of brightly hand-colored printed illustrations. Culled from a series of British children’s chapbooks, the scrapbook’s most recent image appears to date from about 1837 but many of the images are “cuts” created years, even decades before. All the clippings are affixed to pages of linen edged in red silk and are bound in a disintegrating cover marked “Juvenile Scrapbook” and “B. de B. Russell.”

“B. de B. Russell”? Was that a business, place, or person?

We discovered what we had purchased in Connecticut in 2012 was a scrapbook created 175 years ago possibly to mark the birth of a little tyke with a preposterous name. It turned out Blois de Blois Russell was born at the very start of the Victorian era, on June 6, 1837, near Birmingham, England. He rowed crew for St. John’s College, Oxford, and, according to a sniffy email response from the Oxford registrar’s office, he was most certainly matriculated as a “commoner” (not nobility or even a “gentleman-commoner”). We also discovered he died under unrecorded circumstances in 1860 just before his 23 birthday. He seemed to have come from compromised stock as his brother and a sister both died very young as well. Whether being saddled with the name Blois de Blois Russell had any impact upon his health is unknown.

About chapbooks:

Stories, ballads, rhymes and popular tales of piety were passed down through the generations verbally. These oral transmissions started to be written down and printed in the 16th century as broadsides, leaflets and booklets called chapbooks. These were popular, cheap, and cheaply produced texts, typically from 8 to 32 pages and sold by itinerant peddlers called chapmen. “Chap” is etymologically related to an old (Middle?) English word for “trade” (see place name Cheapside in London), and by extension, cheap. Chapbooks specifically for children became popular in the mid-1700s. Chaps were sold plain as printed or colored for an extra cent or two. Who did the coloring? Surely women and children. Pure speculation, but what a Dickensian scene: little waifs with their paint pots working in the dim glow of a lamp, so other, more cosseted children, like B. de B. Russell could enjoy their handiwork...

Now, B. de B. and the Chapbook Alphabet Print Series

We were inspired to create prints with what we found in the album’s pages— mixing letters and images for this series of chapbook alphabet prints. So our first offering is generally agreeable subject matter, just slightly off. Next we'd like to plumb the more macabre offerings-- we welcome any thoughts on the matter.

“B. de B.” wasn't our first choice of names—we went through several—but kept coming back to the euphonious, if odd, B. de B. It had become shorthand for the project, and the name stuck. Now, B. de B. has become a growing collection of historically-based designs that rescues ephemera from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries and re-imagines it for the twenty-first.

See us at www.b-de-b.com

Labels:

art/design,

collections,

ephemera,

nostalgia/remembrance,

words

11.09.2013

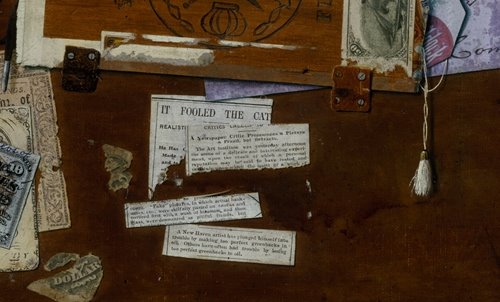

It Fooled the Cat

Artist unknown

Rack Picture for Dr. Nones, 1879

Art Institute of Chicago

William Michael Harnett [1848-1892]

The Letter Rack

The Faithful Colt John Haberle [1856-1933]

A Bachelor's Drawer (and 2 details)

The Slate

I recently did an invitation for the New-York Historical Society for an upcoming lecture called “Trompe L'oeil and Modernity” (see top image here, used on the invite). I'd link to the information but it is already sold out! (but I'm going!) My encore updated post here is very on point:

The book The Arts of Deception: Playing with Fraud in the Age of Barnum by James W. Cook examines the curious strain in 19th century popular culture of illusionism (the self conscious aesthetic and cultural mode that "exists on the boundary between fact and fiction") and artful deception (which employs illusionism but purports to be real). Illusionism pervaded a range of 19th century entertainment, from Barnum's "humbugs," like the Feejee Mermaid, to Paul Phillipoteaux's Gettysburg Cyclorama, through all sorts of magic lantern displays, wax figures and sleights-of-hand. I imagine Cook could include the rage for seances, mediums and spirit images as well, though he doesn't go into these. In Cook's view, the public's passion for deceptive spectacle was influenced by the new "discourse" of advertising, social hierarchies and the expansion of the middle class, and the scientific inquiries of the time. Why was it though, that in a time of exacting definitions of propriety, when morality was strictly parsed and appearances were de facto comments on pedigree, society was thrilled by the questionable, and the ambiguous?

I was particularly interested in his chapter on trompe l'oeil painting--a genre which relied on spectacle. Numerous notices of the time described audiences that gathered to argue, gape at and dispute the nature of the paintings. Many of these paintings were run-away pop-cultural hits. Art critics of any standing, though, customarily dismissed trompe l'oeil work, likening it to the "curiosities" that garnered crowds at dime museums– vulgar and without merit. The work was easily employed in aesthetic and social judgments: if you like this stuff you are a philistine or a rube.

Harnett, Haberle, and Peto --three of the most successful trompe l'oeil painters–often used commercial packaging and other ephemera in their work (like the Dadaists would do literally 20-40 years later). But they were consummate nostalgia-peddlars (a pretty new idea at the time, the sentimental as cottage industry) who incorporated emblems of the West and cowboy life, Civil war paraphernalia, souvenir images of Lincoln, even recalling the good old days beside Grandma's Hearthstone. (Note that Haberle includes a "newsclipping" in his work The Bachelor's Drawer which purports to recount how Grandma's Hearthstone—his earlier painting!— was so convincing a cat curled up beside it's "fireplace"). These visual panoplies of the stuff of everyday life and the traditional home played to growing anxieties in contemporary 19th century society that modernity was erasing a way of life.

The heyday of trompe l'oeil was essentially contemporaneous with Impressionism, and a bit after. Most people think of latter as the aesthetic break-- edgy and avant garde while the former was populist and easily digested. An idea that intrigued me in the book was that trompe l'oeil, while not leading to Modernism, was never-the-less part of a changing visual mode. These sorts of perceptual 'experiments' lead to visual education and redefined the viewer as subjective participant. Visual doubt, essentially, (exemplified in these popular works) was part of the lead up to modernity.

Also worth noting is the fact that yesterday's avant garde (Impressionism) is today's greeting card art, while the overlooked populist work is the stuff of art historical criticism.

See also "I'd like to thank the Academy..." my post on Academic art and silent film.

10.20.2013

a bit of tonic

Cup of Tea, 1905

Bonne Fille, 1906

Helen Carte, 1885

Les Petites Belges (Young Belgian Women), 1907

Still thinking about color after attending APHA's all-day color conference.

An encore post with updates:

A painter I've always liked from afar is Walter Sickert. I say from afar because I never sought out a biography or treatise on him, it was simply that each time I came across one of his works I took note. I am always drawn to his colors: smokey, tenebrous, sharp, acidic. In my mental storehouse of mood and color, however, his choices were always relegated to the appealing but problematic section. His subjects lay in the working classes, the music hall stage, the decadent and alien exoticism of Venice, and most notoriously, in the seamy bed-sit flats of Camden Town in North London and the prostitutes who toiled in them. The moods he captured ranged from the cheerfully tawdry to quiet grimness to the palpably brooding. It wasnt his subject choice that I found problematic, it was something about the atmosphere he conjured up—insistently and consistently—in each work. Is it the sense of remove? Is it the voyeurism? Airlessness? A bit of Sickert is tonic, dwell too long in those visual spaces and one feels a creeping discomfort.

A painter I've always liked from afar is Walter Sickert. I say from afar because I never sought out a biography or treatise on him, it was simply that each time I came across one of his works I took note. I am always drawn to his colors: smokey, tenebrous, sharp, acidic. In my mental storehouse of mood and color, however, his choices were always relegated to the appealing but problematic section. His subjects lay in the working classes, the music hall stage, the decadent and alien exoticism of Venice, and most notoriously, in the seamy bed-sit flats of Camden Town in North London and the prostitutes who toiled in them. The moods he captured ranged from the cheerfully tawdry to quiet grimness to the palpably brooding. It wasnt his subject choice that I found problematic, it was something about the atmosphere he conjured up—insistently and consistently—in each work. Is it the sense of remove? Is it the voyeurism? Airlessness? A bit of Sickert is tonic, dwell too long in those visual spaces and one feels a creeping discomfort.

Sickert was born in Munich to a Danish father and an English mother, but grew up in England. After a brief career on the stage, he became an assistant to James MacNeill Whistler. After 1890 he went to Paris and studied with Degas. Sickert's return to London in 1905 was followed up with a series of nudes that have become inextricably linked with the Camden Town Murder mystery. These paintings and Sickert's perverse sense of self-promotion (calling, for instance, a very equivocal scene of a weary clothed man and sleeping(?) naked woman alternately "What shall we do for the rent?" and "Camden Town Murder") ultimately led to the preposterous theorizing of author Patricia Cornwall that Sickert was Jack the Ripper.

Recently I read a brief but brilliantly written essay about Sickert by Max Kozloff*. In it is one of the most expertly evocative descriptions of color:

...It would be hard to imagine a more distraught monochrome a more neurasthenic sobriety. Whether in its resiny or vaporous distillation, the paint molds into umber purple, degraded violets, emaciated brownish greens, diseased oranges, prussic, somewhat mildewed blues, the whole occasionally enlivened with little splutters of toned-down white, cream or mustard.I find the mental image of that entire palette—degraded violets!— incredibly enticing. Perhaps this speaks to my fascination with Farrow and Ball color charts and my longstanding wish to be paid to research and name colors. How wonderful it would be to have (house) paint charts based on ones favorite painters. Sickert for neurasthenic aesthetes, Milton Avery’s sober olives and grays pierced with oranges, mauves and royal blues for liberal intellectuals with expressionist leanings, Fragonard's nubile pinks and celestial blues for those whose tastes run to more... cheerful titillation. Benjamin Moore take note/

* I should note that this essay is in an obscure and out of print book, The Grand Eccentrics (From Medieval to Contemporary: the eccentric in painting, sculpture and architecture). Many thanks to Malcolm Enright who pointed me to this fascinating collection of essays. An uneven, and in some ways flawed, book it is never the less a terrific storehouse of some great writing and invaluable facts about some of the most riveting figures in art. The book deserves its own post.

10.12.2013

The Tiny Universe of Dot Screens

| |

| all images from John Hilgart's 4CP blog |

Last post I noted the upcoming American Printing History Association annual conference on color. I'm looking forward to seeing Dr. Sarah Lowengard who will present “Why Color? On the Uses, (Misuses) and Meanings of Color in Printing”. From what I know of her she's smart and brings a multidisciplinary philosophical/critical eye to a seemingly narrow subject. I wrote about her, and her fascinating thesis project on color in the 18th century, in an earlier post, Arsenic, Sheep's Dung and a Yellow called Pink.

Another talk that stood out in the APHA roster is Gabriella Miyares' “Worlds, Dot by Dot: 4-Color Process* in the Age of Pulp Comics.” The look of classic pulp comics— cheap paper, ragged printing, colors made up from overlaid fields of dot screens and a welter of misalignments and fortuitous mishaps— is something that resonates in the collective pop cultural consciousness. From Roy Lichtenstein to designers today who ironically try imitating that haphazard mechanical look with the intensive digital precision of Photoshop filters.

Gabriella is a graphic designer based in New York City, working in stationery design but her background experience includes experimenting with letterpress, screenprinting, and intaglio. Last year she attended a

course at the Rare Book School at UVa that had a mini-section on early,

cheap "pulp" color printing, which got her thinking about "how superheroes, and comics, have that very specific

"look" -- those ragged dots and misprintings and very specific color

palettes." Gabriella shared with me some of her research for the talk:

"Hands-down the best visual resource I found was John Hilgart's 4CP blog (http://4cp.posthaven.com/). In looking at these magnified and cropped examples it became clear that the artists were rather limited by a very imprecise printing process, but at the same time the look has become something iconic and beautiful in its own right. That I think was the germ of the idea for this talk. I wanted to explore how these comics were actually made, how much control the artists actually had, and also how emerging technology made this process/look extinct (though it is still imitated with Photoshop!)"... Another incredible visual resource in The Digital Comic Museum (http://digitalcomicmuseum.com/). This website is all volunteer-run by comics enthusiasts who... scan the comics that qualify as copyright-free and post them for anyone/everyone to enjoy. Many of the represented comics are specific genre comics (romance, sci-fi, crime, and propaganda comics) ... I'll be covering the idea of nostalgia in my talk and I think this site is proof of nostalgia for this aesthetic. In the forums you can see a lot of people lamenting that the art of comics today just doesn't match up to the beauty of what it once was -- which on one level is very funny because back then the process was so crazy : colorists basically submitted a watercolor "guide" to a color separation house that would then do all the color, and there was usually no time/money to proof so you just had to hope they got it right...

I'm late to the party in discovering Hilgart's 4CP | Four Color Process: adventures deep inside the comic book site where he scans and artfully crops tiny sections from his seemingly vast comic collection— then blows these up to monumental proportions. His meta- musings on the worlds of dot screens on cheap paper is erudite, lyrical, singularly obsessive, and a little bit whacko. John is a former english teacher and his formidable command of language and literary references spar nicely with the simple subject at hand. His lengthy "manifesto" on "the scopophilic impulse that drives 4CP blog" and on the dot screen itself is well-worth your time and attention. A taste:

[T]he dots provide the visual experience of granular detail that the art itself cannot. Every detail is more detailed, while realism is systematically undermined. Crucially, this perforated universe and molecular level of detail are unintended and have no intrinsic relationship to the illustrative content of comic books. Four-color process delivers surplus, independent information, a kind of visual monosodium glutamate that makes the comic book panel taste deeper.

High-tail it over there.

* "Four color process" is the mechanical reproduction — or simulation—of colors created from overlaying fields of dot screens of cyan, magenta, yellow and black-- the four "process" colors. Comics were printed cheaply and fast in a particularly coarse screen (fewer dots per inch) on pulp paper that absorbed the ink. The resulting registration misalignments, ham-fisted color representation, and ink "bleeding" are what we enthusiasts find so compelling.

* "Four color process" is the mechanical reproduction — or simulation—of colors created from overlaying fields of dot screens of cyan, magenta, yellow and black-- the four "process" colors. Comics were printed cheaply and fast in a particularly coarse screen (fewer dots per inch) on pulp paper that absorbed the ink. The resulting registration misalignments, ham-fisted color representation, and ink "bleeding" are what we enthusiasts find so compelling.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)