skip to main |

skip to sidebar

above, a scene from Caught in a Cabaret with Charlie Chaplin, 1914

above, a scene from Caught in a Cabaret with Charlie Chaplin, 1914

left, "The Return from Toil," working girls as sketched by John Sloan; right, Variété (English Couple Dancing), 1912/13, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner

left, "The Return from Toil," working girls as sketched by John Sloan; right, Variété (English Couple Dancing), 1912/13, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner

Special to The New York Times.Thursday, February 6, 1913

Special to The New York Times.Thursday, February 6, 1913

Mrs. Taft being the President's wife...

A week ago or so at a client meeting I found a book in the "free" pile– Cheap Amusements: Working Women and Leisure in Turn-of-the-Century New York by Kathy Peiss. Published in the 1980s, the book has a very academic and earnest "Women's History" approach which would be enough to turn me off normally, but I particularly got caught up in the chapters on dancing and "Putting on Style."

The first decades of the 20th century brought legions of girls and young women–garment workers, salesgirls, artificial flower makers, tobacco workers– into the work force. Some of these women even lived on their own– a very new phenomenon. The book focuses mostly on working class women who were intrigued by the novel concept of "leisure time", influenced by feminist intimations of the "New Woman" and enticed by a range of modern consumer options.

Most people think of the 1920s as erupting into dance, champagne and louche-ness in a fireworks display of Modernity when in fact, the years leading up to the First World War were rather "fast" and raucous in their own right. Much of the behavior the "Jazz Age" gets credit for had its beginnings before the War.

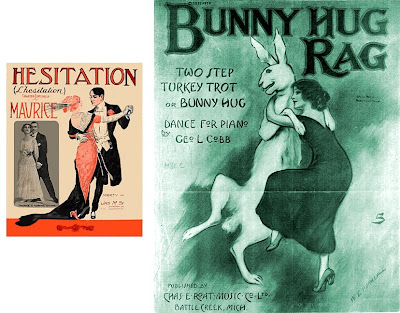

New York was "dance mad." Social clubs and amusement societies held rackets or blow outs at one of the many dance palaces that would hold up to 3000 patrons. "Rough girls" smoked and teased their hair into high pompadours, augmented with puffs and rats. They wore red high heels and exaggerated straw hats drooping under the weight of stuffed birds, and sprays of artificial flowers. They flocked to dance halls, hotels, restaurants for dancing teas and a chance to learn the One-step, the Gaby Glide, the Hesitation Waltz, the Maxixe, Tango, and the Shimmy.

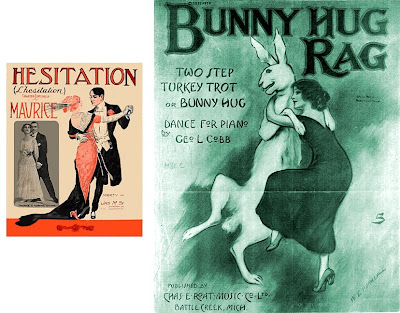

Some of the dances became huge controversial fads and were banned from respectable establishments. The Grizzly Bear, Bunny Hug and the Turkey Trot in particular were said to have originated about 1906 in the brothels of San Francisco's Barbary Coast and were judged vulgar, bordering on obscene. The very worst of the dances invited "much twirling and twisting and easy familiarity...in nearly all the men in the way they handle the girls," according to an observer. "Once learned the participants can at will instantly decrease or increase the obscenity of the movements."

Many venues instituted patrols to maintain decorum and public declarations were made against the new dances. The New York Times of January 16, 1912 reported an announcement at the Hotel Astor "Should there be any of you who have the inclination to dance the grizzly bear, the turkey trot or an exaggerated form of the Boston dip the members of the Floor Committee will stop you."

Investigators sent to prowl the dance halls by the Committee of Fourteen (whose focus was the suppression of commercialized vice) found patrons "smoking cigarettes, hugging and kissing and running around the room like a mob of lunatics." The girls, they found, were "game and lively and sought out flirtation. They go out for a good time and go the 'Limit'".

* * *

"It was the hesitation drag...and never before has there been such a gliding sliding hesitancy; never before such a dreamy drag; never before such a culminating triumph as the whirl, a la pivot. It was supreme; it was new... It was a dance that renounced halos for high jinks, disapproval for complete surrender."

Djuna Barnes– Brooklyn Daily Eagle, September 5, 1913

* * *

What I enjoy most in reading history is when the accrual of a few small casual details suddenly makes the subject recognizable. In an instant a description of "history" becomes knowable, the facts lift from the page. Despite the fact that we see the 1910s in black and white and consider it part of history, it no more felt like or unfolded like "history" than right now feels to us. History is not a place– it is not bound by "the past"– it's simply a stream of everydays.

Recently I saw "Man on Wire," the film about Philippe Petit's tightrope walk between the two towers of the World Trade Center in the summer of 1974. I was slow to warm to the film's charms but the tale finally and completely won me over. Primarily, this is because Petit is an intriguing, exasperating, narcissistic, fairy tale figure. A little prince in many senses, he is both a singular personality and a caricature–as well as very very French. (Which is almost like being a caricature, anyway.)

Recently I saw "Man on Wire," the film about Philippe Petit's tightrope walk between the two towers of the World Trade Center in the summer of 1974. I was slow to warm to the film's charms but the tale finally and completely won me over. Primarily, this is because Petit is an intriguing, exasperating, narcissistic, fairy tale figure. A little prince in many senses, he is both a singular personality and a caricature–as well as very very French. (Which is almost like being a caricature, anyway.)

What I didnt expect from the film was how emotional I would be over seeing so much footage of the World Trade Center: its construction, as backdrop against the city, sweeping aerial beauty shots.

For most of its existence I was indifferent, at best, to the WTC. I have no recollection of actually visiting the towers though I think there may have been a trip to the observation deck at some early juncture. They served a purpose as a visual anchor, a directional on which to get my bearings upon emerging from an unfamiliar subway stop. Other than that, I disliked their needlessly overscaled banality– their crudeness. I had been attuned to architectural grace notes and these buildings were power chords.

It was totally without context, then, that less than a year before they were destroyed I had an abrupt change of mind about the WTC. I was virtually struck in one epiphanic moment. The double towers in tandem, along with their uninviting windswept plaza were one conceptual gesture about scale, less about execution and finish than idea. A simple notion that, for some reason, I had not comprehended, and then I did.

Like lightning rods the WTC attracted Petit's fanatical curiousity. His nearly mystical draw to the towers began with an article he'd read in 1968 about their initial planning and was not extinguished even after completing his mission 6 years later. In the film, Petit recalls his high wire walk as spiritual, a "gift", "elation...I was actually venturing in another world.” The footage in the film shows Petit practically dancing on the wire, weightless, it seemed, and imparting an unexpected delicacy to the colossus he was so barely tethered to. He pulled off this caper, this coup, and managed to bring the building itself into the poetry of the moment.

When he stepped onto the roof after his 45 minute sojourn a quarter mile in thin air he was ambushed by police and reporters. Barraged by what Petit termed a "typically American question" he was repeatedly asked "why did you do it?" The disconnect between the question and the event itself was a sadly comical point in the movie.

Twenty-seven years later in the aftermath of a devastating surreal spectacle people were again asking, "why did they do it?"

Images from top: Tom Fletcher's New York City architecture; "before 9/11" by Baldwin Lee; from wikipedia; from Man on Wire.

The first time I remember seeing a book physically manipulated into a visual display I was hurrying past the window of a shop in Paris 3 years ago. The place was closed so I couldn't find out anything more about the piece or the intent behind it. At the time I couldn't tell whether it was an antique– some kind of Edwardian gentlemen's hobby? a lost folk art?– or a modern work made out of an old book. The piece, in my recollection, resembled that in the photo directly above, with pages folded, tucked and fanned into a geometrical three-dimensionality. I was drawn to its intricacy and mathematical refinement. It was delicate and old-looking yet without frills or baroque curlicues.

The first time I remember seeing a book physically manipulated into a visual display I was hurrying past the window of a shop in Paris 3 years ago. The place was closed so I couldn't find out anything more about the piece or the intent behind it. At the time I couldn't tell whether it was an antique– some kind of Edwardian gentlemen's hobby? a lost folk art?– or a modern work made out of an old book. The piece, in my recollection, resembled that in the photo directly above, with pages folded, tucked and fanned into a geometrical three-dimensionality. I was drawn to its intricacy and mathematical refinement. It was delicate and old-looking yet without frills or baroque curlicues.

I now know there are a number of people creating "book sculptures", "altered books", "book surgeries" or any of a number of terms for books as raw material. It appears to me that some works are "autopsies" – pulling out or highlighting their subject matter visually, eviscerating selected passages– where the specificity of the book's subject or title plays a role (Su Blackwell and Brian Dettmer for instance. Jones calls his site "bibliopath" as in Greek "pathos"– feeling, suffering and "-path": one practicing such a treatment or one suffering from such an ailment). Others simply make use of sheer volume (no pun intended): stacks of bound paper of any sort will do, the more disposable the better. Cara Barer immersed phone books and old computer manuals in her bathtub and photographed the engorged and exploded results. Long-Bin Chen carves stacks of Sotheby's catalogues and phone books into figurative totems. (Truly, is there any other use at all any more for phone books other than fodder for an artist's buzz saw? A physical way of dealing with information overload).

Yesterday a friend mentioned she'd convinced her mother to get rid of a fair number of old books. These had, it seems, long since given up their usable lives to become piles in front of windows and an infringement upon navigable space. I wonder what they could have become in the right hands!

Addenda--now with links...

Images: Cara Barer, Georgia Russell (next 2 rows), Noriko Ambe, Brian Dettmer, Su Blackwell (3 images), Long-Bin Chen, Nicholas Jones (2 images)

images: 30 pieces of silver (exhaled); 30 pieces of silver; Rorschach (endless column 2); work in progress with a steam roller; neither from nor towards; hanging fire (suspected arson); Mass: colder darker matter; cold dark matter: an exploded view; anti-massOn a visit to the otherwise disappointing MAD, I discovered British artist Cornelia Parker (b. 1956). Known for conceptual installation pieces, she has been described as searching for "the elusive essence of material things." It is as though she captures things in moments of disaster, or more specifically, in moments of flux. Stopped in mid-combustion, preserved in mid-fall her work includes objects exploded, flattened, sliced, threaded, washed and suspended. Each work has struck me as surprisingly "alive" despite being in ruin.

images: 30 pieces of silver (exhaled); 30 pieces of silver; Rorschach (endless column 2); work in progress with a steam roller; neither from nor towards; hanging fire (suspected arson); Mass: colder darker matter; cold dark matter: an exploded view; anti-massOn a visit to the otherwise disappointing MAD, I discovered British artist Cornelia Parker (b. 1956). Known for conceptual installation pieces, she has been described as searching for "the elusive essence of material things." It is as though she captures things in moments of disaster, or more specifically, in moments of flux. Stopped in mid-combustion, preserved in mid-fall her work includes objects exploded, flattened, sliced, threaded, washed and suspended. Each work has struck me as surprisingly "alive" despite being in ruin.

Neither from nor towards is a collection of brick remnants from a seaside house which had fallen into the water, the bricks tumbled and eroded by tides. The work I saw, Rorschach (endless column 2), consisted of several pieces of iconic vintage silverware flattened by a 250-ton industrial press suspended a few inches from the floor. Perhaps too easily ethereal and haunting? Still, I found it ravishing. In Shared Fate (1998) she sliced mundane objects (a roll of daily newspapers for instance) with the guillotine used to decapitate Marie Antoinette, among other notables. Her “exploded” work, like Anti-Mass, includes charred remains of churches hit by lightning or destroyed by arson which she has gathered and hung. The particles appear like stardust that absorb light rather than emitting it...

* inanimation: 1) Lack of animation; lifeless; dullness; 2) Infusion of life or vigor; animation; inspiration.

Pietra paesina, also called “landscape stone,” “ruin stone,” “ruiniform marble,” and “Florentine marble” among other names, has been collected for centuries. The “marble” is in fact a type of limestone which when cut into slabs and polished reveals natural veining of iron oxides that resemble –with minimal poetic license–mountainous landscapes, castles, and ruins.

Pietra paesina, also called “landscape stone,” “ruin stone,” “ruiniform marble,” and “Florentine marble” among other names, has been collected for centuries. The “marble” is in fact a type of limestone which when cut into slabs and polished reveals natural veining of iron oxides that resemble –with minimal poetic license–mountainous landscapes, castles, and ruins.

Displayed as natural objects of contemplation in European Renaissance wunderkammer the marble was also incorporated into decorative panels in architecture or furnishings. The stone was sometimes further embellished with painted detail, which, to me, seems sacrilegious.

Ruiniform marble hovers between natural specimen and artifact, abstract configuration and narrative. Its markings are angular, geometric, almost Cubist, vividly etched, yet undefined at the same time. Many stones have the suffused colors of a foggy twilight but some, like the specimen third from bottom, give off the sonorous (yes, sonorous) golden warmth of classical ruins.

How wonderful (in the true sense of the word) it must have been that first time to cut into something solid and “see” the spiritous atmosphere, to peer into something small and see distant wide vistas.

Images: St. Francis exorcising demons from Assisi, Giotto, c.1297; View of Delft, Vermeer, 1659-60; my specimen, which I had framed, was purchased a few years ago from Claude Boullé Galerie 28, Rue Jacob, in Paris.; 3 sample pietra; at bottom is another variant of pictorial stone, Cotham marble, quarried near Bristol, whose striations usually evoke natural landscapes of trees and stormy clouds.

left, "The Return from Toil," working girls as sketched by John Sloan; right, Variété (English Couple Dancing), 1912/13, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner

left, "The Return from Toil," working girls as sketched by John Sloan; right, Variété (English Couple Dancing), 1912/13, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner